It was an extraordinary week for Chinese military corruption headlines. On Thursday, December 5, 2024, China’s President Xi Jinping himself, no less, “stressed the need to enforce discipline and fight corruption in the military.”

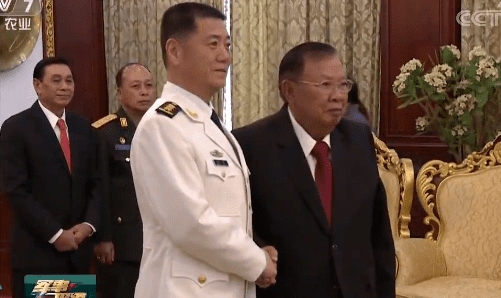

This capped the dual shocks in late November of the firing and investigation of Admiral Miao Hua, head of the Political Work Department of the Central Military Commission, and the investigation of Defense Minister Dong Jun.

Politruks

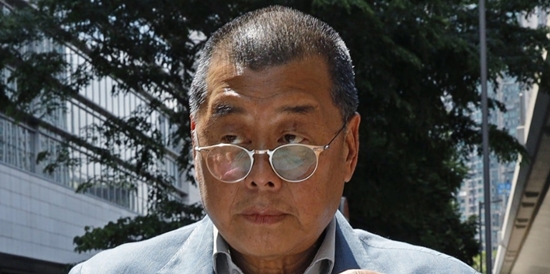

Miao (shown above in foreground) is not exactly a fighting admiral. He is what we used to call a “politruk,” a political officer attached to the military. Miao was the boss of all politruks in Red China’s armed forces, a position that allowed him to make and break officers.

A Western report said that Dong was under investigation but was asked to stay in his post in the meantime. Beijing’s foreign ministry denied this, calling the claim “shadow chasing.”

Miao was a protégé of Xi and Dong was a protégé of Miao. This has generated stories on the themes of “who can you trust?” and “can you believe how widespread is this corruption?”

On the “widespread” side, there is Lyle Morris, foreign policy and national security fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute, who says that corruption in China’s military “is not a case of a ‘few bad apples.’ It is part of ‘doing business’ in the PLA to a much greater extent than most other military organizations around the world, where the rule of law and checks and balances can serve to expose major acts of nepotism and corruption. Despite Xi’s best efforts, corruption in the PLA will endure and bedevil Xi and his successor for the foreseeable future.”

Okay, given that corruption is a constant, can it be that corruption is actually bedeviling Xi? Careful readers will pay attention to another term that turns up in these stories: purge. Purge has political weight.

You can find academic papers addressing Xi’s early days that say he used anti-corruption campaigns to purge military opponents of himself and his policies.

Thus, military “corruption” could be a catchall phrase or a smokescreen that mischaracterizes the purpose of all or most of the firings.

Words

The U.S. Navy offers an example in its use of boilerplate language to obscure the particulars of its many and ongoing reliefs of high commanders. It generally refers to no more than a “loss of the trust and confidence in the officers’ ability to command.” As of June 2024, the Navy fired 12 commanders under this rubric. The Navy fired 15 last year.

We don’t count this kind of thing as a purge, and yet some of the men and women relieved may have been punished for violating political edicts, a purge-worthy offense. “Loss of trust” suggests some professional failing. Upholding standards: admirable. Political purge: ugly.

For, Xi, then, taking a “corruption” hit may be preferable to taking a “purge” hit. Conducting a cleanup is admirable, heroic even. Conducting a purge is nasty.

When we look at Xi’s own language addressing what is being called corruption, it is very telling.

Speaking in June 2024 in a military setting, Xi said: “There must be no hiding place for corrupt elements in the army.” Corruption, though, appears to be but one problem among many. For he also said: “Cadres at all levels, especially senior cadres, must show up and have the courage to put aside their prestige and expose their shortcomings. They must deeply self-reflect…make earnest rectifications, resolve problems at the root of their thinking.” This language addresses ideology, not lawbreaking. When Xi refers to “deep-seated problems” in the military, it is problems—plural, not singular—that concern him.

Barron’s quotes an AFP report that had these interesting takes on reports about corruption and firings:

● Ankit Panda, Stanton Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “Xi appears to be chronically distrustful of his most prominent military officials.”

● Victor Shih, expert on elite Chinese politics: “Competition for top positions is so fierce that there might be some mutual recriminations between officers which would lead to endless cycles of arrests, new appointments and recriminations.”

In December 2023, stories spoke of the “nine PLA generals removed from the legislature.”

In November 2024, Barron’s reported that “nearly 20 military and defense industry officials [were] removed since summer 2023.”

This month, India Today reported that “nearly 100 senior officials have been removed or are being investigated for corruption. These purges are seen as part of Jinping’s broader strategy to consolidate control over the PLA and eliminate potential rivals.”

Realities

There you have it. The corruption campaigns are too small and too targeted and entail too much cherry picking to reflect a general cleanup of the whole mass of corruption in China’s military.

Something else is going on here, and corruption will provide an ongoing rationale “to consolidate control over the PLA and eliminate potential rivals.” □

James Roth works for a major defense contractor in Virginia.