Get ready to swim in quicksand.

“The All-American Myth of the TikTok Spy” (Wired, August 9, 2023) doesn’t really say much about the TikTok app, its relationship to ByteDance, a China-based company; about the relationship of Chinese companies in general and ByteDance in particular to the Chinese Communist Party; about the nature, agenda, and track record of the Chinese Communist Party; about TikTok’s track record implementing the CCP agenda with respect to propaganda, censorship, and collection of personal data; or about how the CCP might use and abuse such TikTok-collected data.

Here are some of the things that author Yangyang Cheng does tell us in the article:

● Slightly amused by a form that a national laboratory required him to fill out disavowing participation “in a foreign talent recruitment program,” he was tempted to scrawl “D-I-S-S-I-D-E-N-T” on the form.

● He has never liked the word “dissident” or “claimed to be one, though others have labeled me as such.”

● Because he was born in China, some people have treated him “as a potential spy before I’m seen as a human being.”

● “Espionage was once considered antithetical to American individualism.”

● “Three decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, as China emerges as a new superpower and contests US hegemony, the face of foreign espionage in the West has become Chinese.”

● The “tint of racialized suspicion has seeped into anything ‘made in China.’ ”

“Racialized suspicion”? Are Americans similarly suspicious about Taiwanese tech produced by companies that don’t answer to the CCP?

● The author believes that Americans are silly to be worried about Huawei and TikTok or to worry when Chinese companies buy up of land near U.S. military sites.

Can we know that worries about these things are misguided as soon as the worries are stated, on the basis of these statements alone—presumably, patently ludicrous statements—or is further inquiry warranted in light of what we know about the Chinese Communist Party and its history and ambitions?

● “Each time an objectionable act becomes racialized, such as how ‘crime’ is coded as Black and ‘terrorism’ as Muslim [a race?] after 9/11, the problem is not that every individual from the minority group is innocent but that the collective is regarded as uniquely guilty, and anyone who shares the identity is implicated by association. The ethnicization of espionage in the US as a distinctly Chinese threat is rooted in centuries-old Orientalism and reinforces racial stereotypes.”

Racism or any form of collectivism is bad. Assumption of guilt by association is bad. Collectives don’t think (or avoid thinking) and act; individuals think (or avoid thinking) and act. But the author is conflating different questions. Individuals may be influenced by a shared culture or philosophy. Is it relevant, for example, that modern radical Islamists preach terrorism for the sake of achieving Islamist goals? That many Muslims in varying degrees accept such rationalizations? Is this something we may talk about? Or should we not talk about it for fear of seeming to indict innocent Muslims?

If the Chinese government poses a major threat that must be countered, there is no way to do it without actually thinking about, talking about, and acting to counter the threat posed by Chinese government, which is staffed by Chinese. Opponents of CCP oppression and murder did not do the staffing. Some foes of the CCP may be racist. But there is nothing about opposing the CCP and working to counter the threat of the CCP that is intrinsically racist or that can be motivated only by racism or race-consciousness. If such opposition is and must be a matter of “racialized suspicion,” why haven’t all other Asian governments been “tinted” by this same suspicion? Why don’t American sounders of alarm about the government of China generally sound the same alarms about the governments of South Korea or Thailand?

Of course, most or all governments, of whatever color, can be fairly criticized on some substantive grounds or other. On the other hand, they’re not all rounding up Uyghurs into murderous “reeducation camps” or chronically threatening neighboring countries.

● The famous journey of China’s spy balloon across America evoked a lot of hot air; “the mass hysteria had less to do with the balloon itself—even the Pentagon acknowledged it posed minimal risk—and more to do with the state of the national psyche.”

The author does not provide details of the hysteria; perhaps the allusion is to criticisms of the Biden administration’s reluctance to stop the balloon as it wafted across America and past military installations.

The detail about what U.S. government officials “acknowledged” is selective. Months before his own article was published, CNN was quoting a “senior State Department official” who said that the balloon “ ‘was capable of conducting signals intelligence collection operations’ and was part of a fleet that had flown over ‘more than 40 countries across five continents.’ ”

“We know the PRC used these balloons for surveillance,” the official said. “High-resolution imagery from U-2 flybys revealed that the high-altitude balloon was capable of conducting signals intelligence collection operations.”

Signals intelligence refers to information that is gathered by electronic means—things like communications and radars.

Do all such concerns and considerations amount to “mass hysteria”? What about China’s prolific other incursions and crimes? Also products of mass hysteria?

● “The illusion of protection by discriminatory means obscures fundamental questions about our relationships with technology and the state, as well as how to navigate between our intimate and communal selves.” What are the discriminatory means? Who or what is being discriminated against? Are Americans “discriminating against” threats to the United States and Americans? And if we are, should we instead be handing weapons to the Chinese Communist Party? Would a white flag suffice?

● “The projection of one’s insecurities onto the other is always riddled with contradictions. In the West, the Chinese people are portrayed as both primitive—so they need to steal technology—and scientifically advanced, with superior spying capabilities.” Contradictions are certainly untenable if they really are contradictions. Is it possible for a government to both steal technology and be sophisticated or at least extremely determined in using it to surveil and repress? Is the complicity of Western tech companies in helping China develop its surveillance relevant here? Or are we doomed to wade eternally through socio-psychobabble about projection of insecurities “onto the other” rather than consider any pertinent facts?

● “The people of China are regarded as so radically different they’re relegated to a different temporal plane, while the present belongs to the West.” Citations would really help at this point. Also, define “temporal plane.”

● The author briefly refers to the “police stations” that the Chinese Communist Party has set up in foreign lands, including the U.S., in part to track Chinese nationals. “Weeks after the press conference, the FBI arrested two men associated with the office in Manhattan on charges of conspiring to act as foreign agents and destroying evidence. On the same day, the Justice Department also charged 44 individuals, believed to be based in China, on crimes related to online harassment and intimidation against Chinese nationals in the US.”

Taking this flatly reportorial passage in isolation, the reader can detect no note of self-distancing skepticism and no assumption that the reported conduct of the Chinese Communist Party is all just a ridiculous fantasy, a phantasm upchucked by mass hysteria. But this respite does not last. The author soon feels a need to stress what he regards as the revelatory irony of a “prop” used by Chinese protestors against transnational repression: a pale balloon symbolizing the spy balloon that he regards as having inspired “mass hysteria.” He also feels a need to assert that the experience of being targeted by the CCP is more or less in the same category as the experience of “being a racialized minority.” Yangyang Cheng writes:

For those of us who have crossed oceans and political systems, to still live under the watchful eyes of the home government can be a profoundly lonely experience, not unlike that of being a racialized minority. In the words of a Chinese human rights activist who spoke at the rally, “This is the first time that the Chinese basic community feel that their grievance is heard by the American public.”

The author doesn’t seem to realize why it is possible for the foes of the CCP to regard the victims of the CCP’s “watchful eyes” as victims of the CCP even though those victims are themselves Chinese and therefore, supposedly, on the receiving end of a “tint of racialized suspicion.” He has not provided any evidence of how this “tint of racialized suspicion” corrupts understanding of the Chinese government and its policies, and he is inert to any evidence that seems to contradict the determinative power of this imputed tint.

Contra Yangyang Cheng, it really is possible to observe and oppose the viciousness of the Chinese party-state as manifested by its actual conduct, and on the basis of an ethics that upholds the value of life and freedom rather than on the basis of irrationally nurtured tints of racialized suspicion.

● The author makes much of the fact that the United States government has not stopped U.S. companies from collecting and abusing the data of Americans but now wants to stop the CCP from doing so.

I would not argue that the policies of the U.S. government are infallibly consistent. But is Western surveillance exactly the same kind of threat to individuals as CCP surveillance? To the extent that U.S. private companies are acting to violate the rights of individuals, alone or in concert with the government, is it not possible to oppose such violations while also opposing the threats of the Chinese Communist Party?

In confusing conclusion

The grand finale: “What if safety is achieved not by violent organs of the state but through their abolition? What if we reject the false binaries proposed by status quo powers and choose liberation? What if, instead of imprisoning our identities within predefined labels, we refuse to be categorized? What if we make ourselves illegible to convention, corrupt the code, glitch the mainframe, and disrupt the ceaseless flow of datafication? A secret language opens up pathways to fugitive spaces, where an uncompromised presence is restored and alternative futures are in rehearsal.”

Now all specifics, however distorted, have faded into the mist, and the author gives us only airy, undefined, detached anarchist abstractions by way of recommending a course of action.

Does the author want the U.S. government to shut down its military while the Chinese state maintains its own military? Or what, exactly?

Is the author planning to disrupt the flow of datafication by hiding in the woods, by no longer filling out forms? Or what, exactly? And what is the relevance of such steps to understanding of the CCP and TikTok?

How do we make ourselves “illegible to convention”? Does this mean we must speak Hittite in response to comments about the weather? Or what, exactly?

But it would be folly to ask the author to lapse into facts, logic, and clarity at this late point in the article. He is fully liberated and illegible.

Does any of this bring us any closer to an objective and judicious assessment of the threat posed by TikTok, which insofar as the mere evidence tells us, the Chinese Communist Party is using as a weapon? One gets the impression that Yangyang Chen doesn’t really care about this question, which, ostensibly, is so crucially relevant to his asserted theme, that the threat of TikTok is a myth. He does not review the evidence. Indeed, so much of his article is diversionary and obfuscatory that one is obliged to suspect deliberate dishonesty.

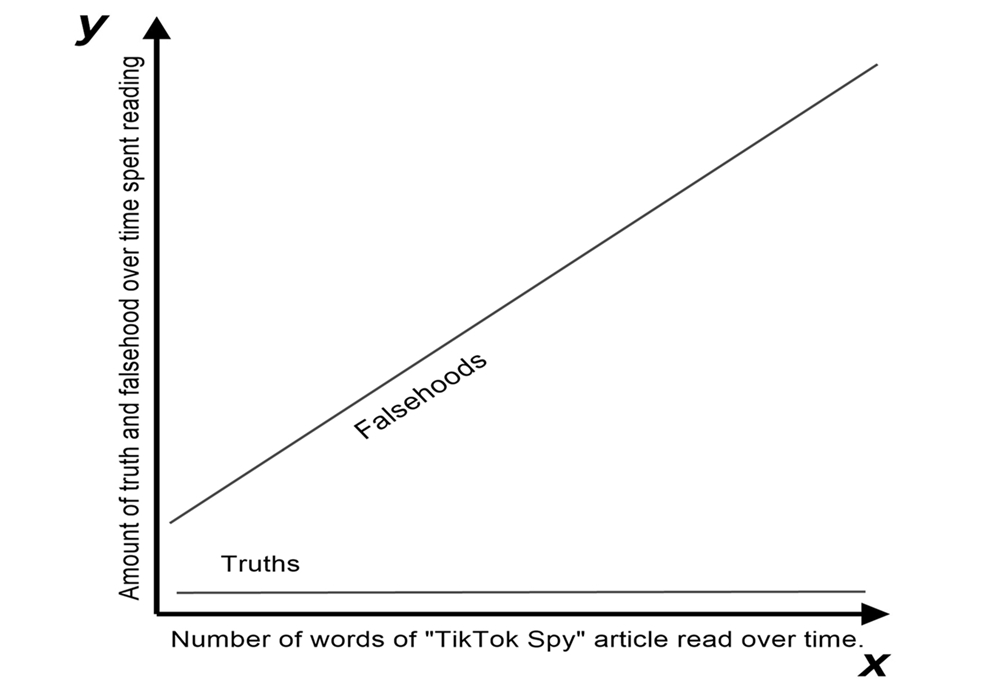

In the chart preceding this article, I illustrate the relative proportions of falsehood and truth in Yangyang Chen’s article as they change over time during your reading of his article.

As you can see, the more words of the article you read, the more falsehoods you are exposed to. Whereas what scant incidental truth the article contains remains incipient throughout and is always immediately suffocated by a surfeit of falsehood. The more you read, then, the greater the ratio of falsehood to truth you must suffer.

Perhaps you can learn something about the mentality of the author by reading “The All-American Myth of the TikTok Spy.” But you cannot learn much about why anybody would regard TikTok as a threat or, for that matter, would regard the Chinese government or Chinese Communist Party as a threat. The American government, like the Chinese government, spies and monitors. Americans, like the Chinese, are aware of race. American policies are inconsistent. That’s it?

Also see:

StopTheChinazis.org: “China Pans U.S. Plan to Tackle TikTok”

“China could shoot you in the heart while protesting that you’ve yet to show that it is aiming a gun at you and pulling the trigger.”