The harassment of Li Ying, his family, his friends, and his Twitter followers is one of the reasons he spoke to the BBC.

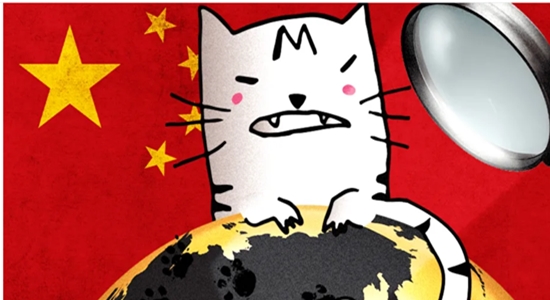

“By going public with his allegations, he hopes to expose the Chinese government’s tactics. But it’s also because he believes they crossed a line by escalating their repression.” He wants to fight back. (“A cartoon cat has been vexing China’s censors,” June 9, 2024.)

For some reason, the Chinese government “has not responded to our questions,” says the BBC. Nor has the BBC been able to independently confirm all of what Li reports. But the harassment he describes is all too plausible, standard operating procedure for China’s transnational repression.

And Li’s massive online presence—he’s currently got about 1.5 million followers on Twitter—make him a big target.

Teacher Li is your teacher

The point of the Twitter account (called in English “Teacher Li Is Not Your Teacher”) is to report on things that China tries to censor, like the horrors of the lockdowns, criticism of the government, protests against the government, arrests.

Li, who lives in Italy, where he had gone to study art, says that he is an ordinary person who became what he is now almost accidentally. He didn’t think that the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong “had anything to do with me.” But he was shocked by the pandemic lockdowns in China and began reporting on them in his Weibo account. “There were people starving, even jumping off buildings.”

Chinese censors blocked his Weibo account. He got a new Weibo account. They blocked the new one. He got another one. They blocked that one. After this had happened 53 times, he decided “Okay, I’m going on Twitter.”

On X [Twitter], unfettered by China’s censors, yet accessible through virtual private networks, Mr Li’s following grew. But it only really exploded, to more than a million, in late 2022 during the White Paper protests against China’s punishing zero-Covid measures.

His account became an important clearing house for protest information; at one point, he was deluged with messages every second. Mr Li hardly slept, fact-checking and posting submissions that racked up hundreds of millions of views.

Online death threats from anonymous accounts soon followed. He said the authorities arrived at his parents’ home in China to question them. Even then, he was sure life would return to normal once the protests died down.

“After I finished reporting on the White Paper movement, I thought that the most important thing I could ever do in this life was finished,” he said. “I didn’t think about continuing to operate this account. But just as I was thinking about what I should do next, suddenly all my bank accounts in China were frozen.

“That’s when I realised—I couldn’t go back anymore.”

In addition to interrogating his friends and family, Chinese police also managed to track down some of his Twitter followers. “Of course I feel very guilty. They only wanted to understand what is going on in China, and then they ended up being asked to ‘drink tea’ ” (a euphemism for being subjected to police questioning).

When he let people on Twitter know that this was happening, “overnight, more than 200,000 people unfollowed him.”

Ordinary guy

“I don’t see myself as a hero,” Li says. “I was only doing what I thought was the right thing at the time. What I’ve demonstrated is that an ordinary person can also do these things.”

Far from being cowed, Li says that “until they find me and pull me back to China, or even kidnap me, I will continue doing what I’m doing.”

Li has plans to expand. He may enlist the help of others, may also publish in English. The Chinese government “is really afraid of outsiders knowing what China is really like. [Posting in English] is something they are even more afraid of.”

Also see:

Twitter: 李老师不是你老师 (Teacher Li Is Not Your Teacher) @whyyoutouzhele

YouTube channel: 李老师不是你老师 (Teacher Li Is Not Your Teacher)

The videos and messages of these two channels seem to be all or mostly in Chinese, but at least the text messages can be translated using Google Translate.