One way to say things in Chinese social media that the Chinese government prohibits you from saying is to disguise your hashtags. The idea is that your readers will realize what you’re up to but that the censors and their software will not, at least not right away.

The trick is explained by Prajakta Athlekar, a student specializing in something called Digital Culture Studies. She frames her report by saying that she will be “using Doug Belshaw’s concept of digital literacies [to] analyze how Chinese activists navigated the digital sphere and bypassed China’s great firewall. . . . In digital literacies, the process of meaning-making relies heavily on context” (diggit magazine, September 25, 2023). So kind of like literal literacy then.

In 2018, a former student at Beihang University accused a professor of sexual harassment on Weibo, a large social media platform in China.

Her post attracted around 4 million views and 16,000 shares by the next day (Abbott, 2019). Following her post, many Chinese women started speaking up against their harassers and spreading public awareness of sexual harassment. They began using #MeToo and #WoYeShi, which is the Chinese translation of #MeToo, on several other online platforms like Weibo and WeChat. . . . A few days into the movement, authorities started blocking those hashtags, deleting relevant posts across all social media platforms and any content related to #MeToo in order to avoid any more public discussion. . . . Since authorities had banned any keywords related to #MeToo or its Chinese translation, the activists came up with their own version of #MeToo to bypass censors and avoid the risk of being flagged. . . . [They used] visuals, signs, symbols, and playful manipulation of old hashtags. . . .

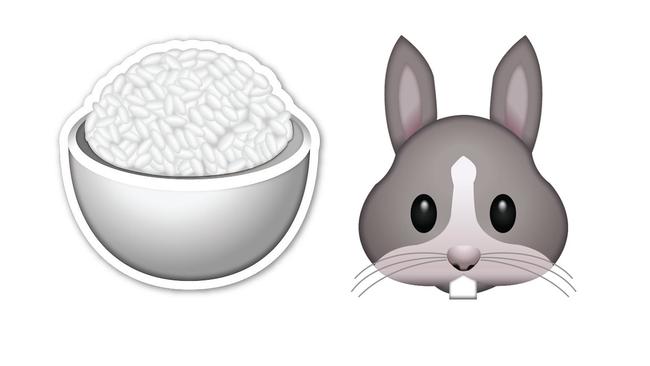

They began using #mǐtù (#米兔), which is a homophone for #MeToo. . . . In Mandarin, mǐ (米) means rice, and tù (兔) means bunny, which translates to rice bunny. Soon that was blocked by the authorities. To trick the censors and algorithms, Chinese activists started creating other variations of #mǐtù, such as emojis of a rice bowl and a bunny together (Yang, 2019). . . . Illustrations or emojis are not easily detected by automatic censors and need to be manually censored.

Two other methods of eluding the censors and their algorithms mentioned by the author are content-caching and image-rotating.

If recent history is any guide, China’s censorship software will only get better and better at detecting patterns of censorship-evasion. On the other hand, where there’s a digitally literate will—and any lag at all between communication of forbidden things and censorship of the communication—there’s a way.