How vexing to lose power in one room, my office, for one day. Until the rust-frozen lock to the circuit breaker box could be busted open and a lever pressed to restore the interrupted circuit—thanks, neighbors—I had to rough it, resorting to flashlights, the light of other rooms, a laptop, procrastination, and similar desperate makeshifts.

Because of hurricanes, I’ve also on occasion uncomfortably survived without any electrical power at all for a day or three. But when such things happen, the local power companies scramble to get everything back up and running, and crewmen from other places also come to help out. Usually, things are more or less back on line for most people within days or weeks. It is all very heartening—except for the complaints about and penalizing of “price gouging” when vendors charge higher prices for things in suddenly short supply, increases that when allowed to function encourage both economizing by consumers and further efforts by producers to expand abbreviated reserves. (You choose: “I had to pay a ridiculously high price for this thing I urgently need!” Or: “I was unable to find a single unit anywhere of this thing I urgently need!”)

Another possibility is a coast-to-coast outage that lasts many months because of rickety electrical infrastructure and corrupt political infrastructure, everybody living near the ocean, and so forth: Puerto Rico in 2017. It took most of a year for everyone in the territory who had lost power when Hurricane Maria hit to somewhat get it back.

What if a power outage lasts even longer and affects a much wider area thanks to a massive electromagnetic pulse (EMP) or coronal mass ejection (CME), or some comparably pulverizing event? One that, for example, cripples the mainland United States but leaves the other side of the world alone?

Most of the nation’s power grids go out. Backup supplies of parts needed to fix the grid are not on hand for the most part, and many of these crucial parts must be gotten from China. Which for some reason is reluctant to provide them. Now what?

The so-called Carrington event of 1859 was the preview. A CME “caused widespread damage to the national telegraph system, in some cases starting fires and delivering electric shocks to telegraph operators,” writes Aaron Larson in an April 13, 2023 article for PowerMag.com. “A CME in 1989 that was far smaller than the Carrington event tripped Hydro-Québec’s La Grande high-voltage transmission network,” causing “widespread power outages and damage up and down the U.S. East Coast.”

The risk of another Carrington-class CME striking the Earth is not clear, though it is thought to be [likely to occur] about once every 100 to 200 years. A CME of at least that magnitude was observed in 2012, but it missed striking the Earth by about nine days because the solar flare was oriented in a different direction. [William] Forstchen noted that the U.S. power grid is vulnerable to such an event for a number of reasons. “The average component in our electrical grid is 40 to 50 years old. We are running our electricity on a 1970s, early-1980s industry. We’re not modernizing it,” he said.

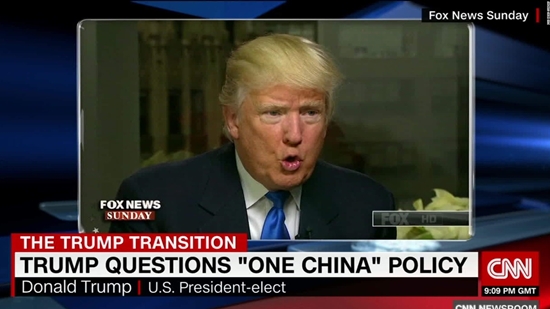

A few years ago, the federal government began to address the problem. “The Trump administration finally started taking action about six months before the election in 2020. They mandated DOD, DOE, all the different agencies to submit a comprehensive analysis of what needs to be done that would then [be followed] by legislative action in the next Congress,” Forstchen explained. However, when Trump lost the election, President Biden immediately killed the initiative, he said.

Forstchen said relatively minor investments could vastly improve the situation. He suggested stockpiling key components is an important first step. “A large transformer for a major substation can cost several million dollars. From the time of ordering one until the big truck pulls up and we start to unload it is two or more years,” Forstchen said. Furthermore, he noted that most of the equipment and components that might be needed to repair the grid are now sourced from other countries, mainly China, which means the U.S. may not be able to get supplies, especially if the attack was initiated by one of those countries. “We should be building a strategic reserve of key electrical components,” he said.

If “most of the equipment and components that might be needed to repair the grid are now sourced from other countries, mainly China,” and one day most or all of the American power grid gets knocked out, and China says, “Geez, we have other uses for this stuff at the moment, but look, mankind has always made progress by surmounting difficulties, let’s walk together toward the bright shared global future, bye now,” it will not be good.

It would be dumb to even ask China for any power-grid components if it’s China itself, trying to hurry along the shared global future, that has caused the continent-wide outage—perhaps by flinging a flock of hypersonic missiles at us before the U.S. has developed even a single one.

Fortify power grid fast, develop hypersonic missiles at hyper speed…what else? Probably a long list.